Daniel Browning

“On Ali Tahayori”

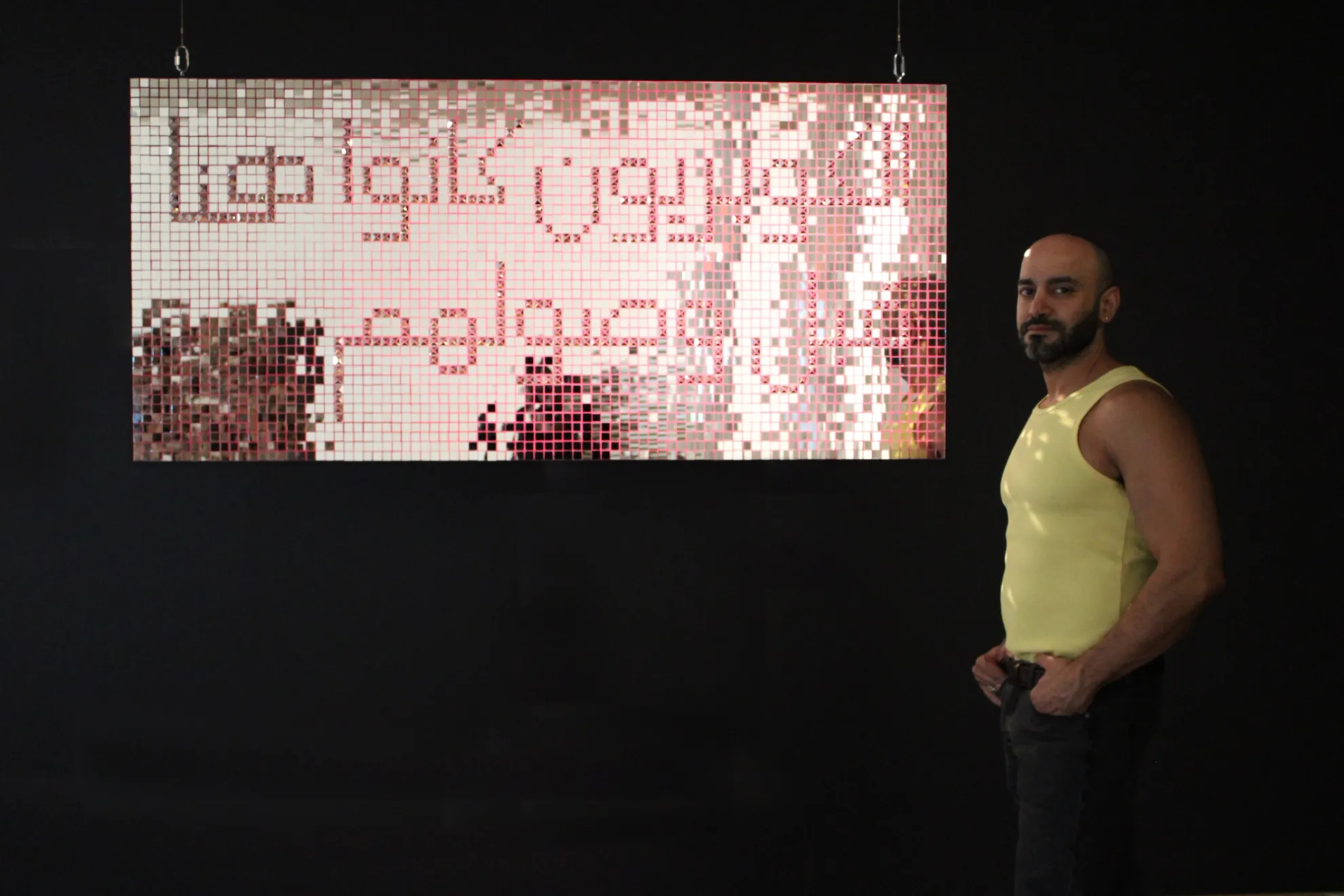

I experience a range of emotions when I confront an artwork by Ali Tahayori. My use of the term is deliberate. There is a challenge in his artworks as inherently social acts produced for public consumption, whether the work in question is one of his distinctive, handcut mirror text pieces, his black and white photographic images diffracted under glass or his poetic video installations. There is no value judgement in my use of the term - a confrontation isn’t inherently negative, but there is a sense of being challenged to extend myself to see something that is not visible. Something subtle, or obvious. Given the static text works often use glass mirror tiles – a queer visual language if ever there was one, both tawdry and glamorous - the confrontation I experience is often with myself, or at least a splintered, broken reflection of the physical self. As a friend, I understand there is something being put to the viewer, and I respect the artist enough to listen.

I think of one of his most recognisable signature works, Objects in Mirror Are Closer Than Appear (2022), acquired by Artbank and currently on show in Melbourne. There is something quite confronting, even threatening, in that apparently neutral yet cold statement of fact; the driver’s warning we generally might read on hulking road trains as we pass on the highway assumes a different meaning out of context in a white cube. It could be that we are closer to strangers to whom we feel nothing but indifference, even towards those we seek to differentiate ourselves such as our competitors or even our enemies - perhaps we are more like them than we think. Our common humanity bonds us, even if we perceive them as ‘objects’ - the distance is not the yawning gulf we imagine. Indeed, we are so close as to be at risk of collision.

In There Were Queers Here Before They Arrived (2025) Tahayori strikes a blow at the misuse of the rainbow flag to legitimise violence, and its cooption as an empty device virtue-signalling ‘Western’ values of freedom and democracy. The ‘here’ is any non-Western society which we might suppose has no tradition of, or movement towards, gay liberation. Tahayori fled his homeland, Iran, in the first decade of this century as a young man and has spent almost 20 years as a sexual dissident refugee or forcibly displaced person - one who is unable to return, and who gave up everything for the liberty of his body and the freedom of his mind. Iran is a theocratic state, patrolled by morality police and overseen since the Islamic Revolution by a succession of ayatollahs – ‘supreme leaders’ - senior Muslim clerics with personality cults who preach contempt for queers. The declaration in the work is somewhat encrypted – unless you can identify the calligraphy. The florid horizontal Arabic script is Kufic, Ali tells me, in which the earliest versions of the Qu’ran were inscribed. Tahayori rarely overstates his politics, yet here he also confronts the state-sanctioned homophobia that forced him to flee his homeland, as much as the pinkwashing, virtue signalling and misappropriation of the rainbow flag. Once asked about the repression of sexual difference in Iran, then President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad contradicted his questioners in the foreign media by saying there was no repression of homosexuality because there were no homosexuals in Iran.

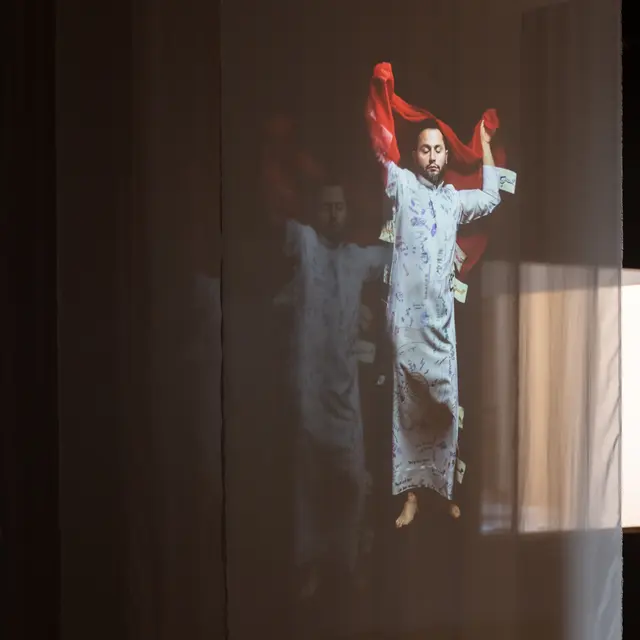

It’s hard to imagine the Ali Tahayori I know and love repressing anything; his restlessly creative spirit, his independent, problem-solving mind and his voracious lust for life are some of his most defining characteristics. His dissidence, forced migration from Iran, exile and statelessness are often elided altogether in his work; instead, he makes images of fragile beauty, of terminal longing, of a more liberal Iran, of loss and separation, bittersweetness, of queer possibility and infinite joy. He once quoted a line from his favourite poet Hafez (1320-1390), a Sufi mystic who like Ali was a native of the historic city of Shiraz in southeastern Iran and who wrote of same-sex love at a time in Persian history when homosexuality was not the subject of fervid moral panic, social phobia, persecution and state-sanctioned violence. Ali said that the poet’s great struggle - I’m paraphrasing here – was between two polarities, always in suspense: grief and anticipation, loss and hope, separation and union. The grief of separation is counterposed by the anticipation of union, or reunion, with the beloved (whoever that is). The paradox stayed with me, and ever since it has only deepened in meaning in relation to my own life. Almost immediately, I wrote Ali a poem – which I promised never to share with him, as once shared, my poems seem to have a toxic effect. I was simply expressing my joy at our blossoming friendship, the vulnerability and the possibility of it (NGL my friendship circle is more of a segment). At least for me, Pride Square captures the mood between us now as it did then.

“I’ll wait for you at Pride Square”

You wrote

Let’s always meet there

Where our hearts billow

like cloud

Unfurling across the burnt orange

of an inner west sunset

If I was a skywriter

I would spell out

Across the perfect mid blue of the southern sky at noon

in wispy letters ten storeys high

A message to you

alone

My promise, my oath, my will

Everything that is true

If life brings us only separation

And never union

Know this خوشتیپ

We are forever.

Daniel Browning is an Aboriginal writer, journalist, radio broadcaster, documentary maker and sound artist. In his previous role as Editor Indigenous Radio at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, he led the Indigenous Radio Unit overseeing longstanding flagship programs Awaye! and Speaking Out as well as establishing the language revival podcast Word Up. A visual arts graduate and self-described “failed artist”, Daniel went on to host The Art Show and Arts in 30 podcasts, soothing ABC audiences with a voice once described as “like honey dripping over a rock by a rainforest stream”. In nearly three decades at the national broadcaster, he worked as a general and specialist arts reporter, digital journalist, newsreader, sub-editor, producer, presenter, manager and senior executive across several divisions including News and Current Affairs, triple j, ABC Indigenous and Radio National. Daniel is a widely published freelance writer, public interlocutor, arts communicator and cultural critic.