Behrouz Boochani

“On Elyas Alavi”

I have known Elyas Alavi for years through his poetry. The first poem that still stays with me — and I believe is probably his most well-known work — includes this phrase:

“As you draw water from the well

And make tea with that water

Doesn’t it taste like blood?”

This phrase marked the beginning of my journey with Elyas’s works — a journey that still continues. Through the Iranian-Australian artist Hoda Afshar, I was later introduced to other works by Elyas, which eventually led to meeting him in person and building a friendship.

Regardless of the power of imagination and visuality in Elyas’s poetry in terms of form, what has always impressed me is the purity and freshness of the feelings in his words. When I met Elyas for the first time, my first question was how is it possible for him to keep the essence of a feeling or memory that later turns into a poem?I think capturing deep emotion is the core of his artistic language, and to achieve this, he often relies on memory and the re-imagination of memory.

For an artist and poet like Elyas, who has experienced a long history of displacement and movement between places, and also as a Hazara, there is always a stereotype or label that prevents Western audiences from fully understanding his work. There is always a risk of reduction. The image of refugees carries a long and recurrent history of dehumanisation, and Western audiences are often influenced by this image. As a result, they tend to put artists like Elyas into a box and celebrate only the concept of “life experience,” reducing their work to a mere representation of biography.

Often, it seems such audiences forget that every artist has a life experience, and that no artist can create works detached. Yet, when it comes to people from marginalised backgrounds, emphasising “life experience” often reduces their art.

When we look at Elyas’s works, we encounter an artist with multiple languages and skills who develops different layers of worldview and perspective. The core of Elyas’s work, beyond its purity and freshness of feeling, lies in how he relies on memory. He does not use memory as an abstract idea but develops, re-imagines, and re-produces it — linking it with current life or political contexts.

In the project Sound of Silence, 2024 Elyas uses a musical instrument called the rubab, which was once played by cameleers living in Australia at the end of the nineteenth century. He uses this instrument to materialise memory. In another project called Cheshme-Jan, 2023 which refers to Afghanistani cameleers, he uses a book holder to reimagine meetings between cameleers and First Nations people in the past century. Again, we see how he materialises memory — an approach that often appears in his work.

In the project ALAM, 2024 which is about queer Muslims and refers to specific events, we again see how Elyas uses religious elements and sculptures not only to memorialise those events but also to materialise them. When I speak of the materialisation of memory, I mean not only reshaping or reimagining memory but also searching for it.

Elyas uses multiple artistic languages to approach memory. He relies on oral stories and folk cultural elements such as songs and poetry. In this context, poetry serves not only to express meaning or emotion but also as an element of form.

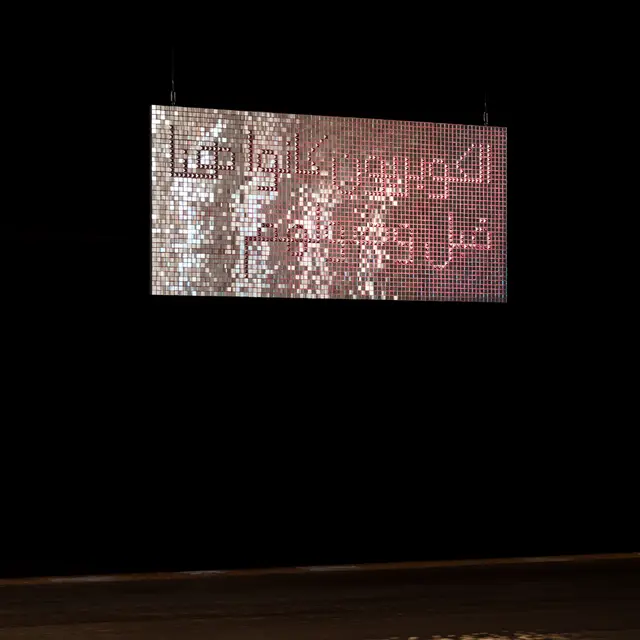

In fact, we should understand the text as a visual element that serves the aesthetic of the work. His poems are often written in interesting and sometimes unusual fonts or shapes, employing color, such as red and blue, to position the text not as something separate from the artwork but as part of it.

Another important layer of Elyas’s work is its intersectional context. As audiences, if we fail to approach these works through an intersectional lens, we miss how deeply political his work is. His works are neither rhetorical nor passive: Elyas does not passively create art based on his life experience alone. Instead, he weaves multiple layers of meaning to form a new centre — this is what makes the work radical.

His works represent displacement, belonging, and the sense of place; war; Hazara collective experience; LGBTQ experience; systemic discrimination; First Nations of Australia; and the broader context of colonialism. We clearly see how he links the experience of Afghanistani cameleers in the past with that of First Nations people in Australia, and then how he connects this to the contemporary systems that still oppress both First Nations people and refugees. He links this colonial mentality to what the Australian army has done during the twenty year war in Afghanistan.

In his poetry about Kurdish people and their search for freedom, he connects their plight to that of Hazara resistance, and beyond to broader knowledges of resistance with other colonised nations. In fact, Elyas draws from multiple forms of resistance knowledge created by minorities and marginalised people within the context of colonialism — linking and sharing them to empower each other. Such an interconnection of marginalised insight is the most radical way to challenge power structures.

Elyas’s artistic language for achieving this radical approach is collage. He uses painting, visual art, video, poetry, folk elements, and other materials to create new forms from existing material. In a video he made about Australian army war crimes in Afghanistan, he uses footage collected from his family’s reunion in Sweden after a decade, combining it with one of his poems written on a wall in Iran to link Iran, Afghanistan, and Australia. He pastes together newspapers, poetry, and painting to represent what has happened to the people of Afghanistan.

In my view, Elyas’s life and his journey becomes a collage. He was born and raised in Daikundi village near Kabul, Afghanistan, later displaced to Iran where he grew up, lived among Baluchi and other marginalised communities, visited Kurdistan, lived in Australia, and experienced solidarity with First Nations people. In his works, there are always pieces from different places and life experiences — like a fragmented puzzle that comes together in his art.

For many, Elyas is an established poet for Farsi readers; for others, he is an artist representing displacement; for some, he tells the collective story of Hazara resistance; and for many, he is a queer artist calling for freedom and justice. Elyas represents all of this together through his abstract works.

For me, as someone who knows him and has followed his work, there is an inner inclination in me, not necessarily logical, that makes me loyal to my first image of him as a poet. I always see Elyas as a poet who extends poetry outwards into other art forms.

Behrouz Boochani is a Kurdish writer, political scientist and internationally acclaimed advocate for displaced people. Educated in Tehran (MA, political geography), spending years inside offshore-processing regime. During that time he secretly composed No Friend But the Mountains via thousands of WhatsApp messages; the genre-blending memoir swept Australia’s top literary honours and is now taught globally.

Boochani’s work spans journalism, philosophy and film. His landmark documentary Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time (2017) offers a raw lens on carceral control, while his latest book, Freedom, Only Freedom (Bloomsbury, 2022), gathers essays and speeches that indict the wider refugee apparatus. Drawing on anti-colonial thought and Kurdish poetic tradition, he reframes displacement as both lived reality and philosophical terrain, revealing how language, memory and art enable dignity amid systemic violence.

Now based in Wellington, New Zealand, Boochani serves as a freelance writer, journalist and film maker.