Channon Goodwin

“Run to Paradise: West Space as a Micro-Utopia ”

Good times

Why'd I let 'em slip away?1

The pursuit of an ideal is serious business and not for the faint of heart. Emerging from Australia’s Artist-Run milieu, West Space is a form of ideal in progress. Successive generations of artists and arts workers have contributed to imagining a better type of arts organisation, and invested their time, creativity, and money into making it a reality. Of course, an ideal is perfection and perfection is unattainable. In this sense, West Space could be considered a micro-utopia in constant making and re-making.

The contemporary concept of a micro-utopia in the arts is most commonly associated with the curator and theorist Nicolas Bourriaud as part of his proposition of relational art.2 Bourriaud set out to interpret a cluster of artistic tendencies of highly participatory and socially-oriented practices that emerged in the 1990s — the same decade as West Space was founded by artists Brett Jones and Sarah Stubbs. The boundaries that delineate relational art from the activities of an artist-run or artist-led gallery are fluid given the heightened sensitivities to the audience and their relationship to both the artist and their work. For Borriaud, relational artwork takes ‘as its theoretical horizon the realm of human interaction and its social context’,3 which results in an emphasis on social interactions and human relationships as integral components of the art experience. Bricks-and-mortar venues like West Space, founded by artists, are unique convergence points for art, artists and audiences. They create a social scene, fostering an ever-evolving hyper-local cultural identity. They are sites for propagating what Bourriaud describes as an ‘everyday micro-utopia’:

Avant gardes were about utopias. How is it possible to transform the world from scratch and rebuild a society which would be totally different. I think that is totally impossible and what artists are trying to do now is to create micro-utopias, neighborhood utopias, like talking to your neighbor, just what’s happening when you shake hands with somebody. This is all super political when you think about it. That’s micro-politics.4

Bourriaud’s contribution was to move utopianism away from lofty notions of future perfect societies and instead emphasise the ‘concrete actualization of the utopian impulse into everyday life’.5 For centuries, traditional conceptions of utopia have been based on Sir Thomas More’s grand humanist vision for a better, classless society, flourishing in the work of revolutionary writers of the seventeenth century, then evolving in the romantic movement of the nineteenth century, and giving rise to twentieth-century science-fiction and dystopian fiction. Out of this literary lineage, the classic utopian narrative emerged offering a way to escape into imaginary alternative societies, always better than one’s own. By abandoning these unattainable utopias, Bourriaud has directed our attention to the real and now, through the localised and socially-based micro-utopias all around us, reminding us that ‘it seems more pressing to invent possible relations with our neighbours in the present than to bet on happier tomorrows.’6

Through this lens, we can better understand the forms of sociability that the artists, audiences and workers practice day-to-day within small arts organisations. The concept of the micro-utopia helps us to locate the elusive moment when a community forms around the shared activity of art making and viewing. The work of Bourriaud’s relational artists, most notably Rirkrit Tiravanija, deliberately seeks to accentuate social relations, interactions and encounters that already exist, especially in the gallery settings at the moment that art, artist and audience coalesce and enter into social dialogue and create meaning together. It is through these temporary communities, as Bourriaud stresses, that ‘alternative forms of sociability, critical models and moments of constructed conviviality’7 can emerge, briefly impacting peoples’ lives in real, immediate and tangible ways.

This is eloquently explained in the journal article, Micro-utopias: anthropological perspectives on art, relationality, and creativity (2016):

Within this framework, micro-utopias appear as (artistic, political) statements that result from the "neighbourhood interactions" of our everyday lives, from the ability to imagine and create in the local sphere, responding to concrete political questions of the present. Bourriaud is thus interested in utopia as a “device” to move away from the abstract and locate the concrete, political component of the micro-dimension of social life, the structures and flows of power and production that conform our everyday lives.8

Further expanding on the practical implications of Bourriaud's micro-utopia and relational art, Tamzin Buchan contemplates the revival of relational aesthetics through an emphasis on Relational Egalitarianism. Buchan points to the revelatory moment during the COVID-19 pandemic of seeing hundreds of thousands of Australians lifted out of poverty for the short time that JobSeekers payment was implemented, highlighting just how normalised it has become for many, particularly artists, to perpetually exist with incomes well below the Australian poverty line. In addition to calling for a basic universal income, Buchan invites readers to create ‘micro-utopias of equality, re-connect with our communities and hope that we can transfer these relational paradigms to the wider social landscape.’9 In times of crisis and disparity, the true value of connection and tangible support becomes more apparent.

Bourriaud’s micro-utopias are, therefore, nutritious entities containing many of the substances needed for a community to flourish. They are intertwined with ideas of communal living, well-being and aspirational political concepts which create experiences that shift entrenched societal expectations by expanding the ‘realm of the possible’. This brings the concept of the micro-utopia into contact with the commons movement, another social model with a long history that is recently garnering attention among artists, researchers and activists. The commons is broadly defined as a shared resource, co-governed by its user community according to the community’s rules and norms. These resources can be as large as civic infrastructure and cultural works, as well as various models of smaller-scale resource-sharing, including community gardens, mutual aid networks, coops, open-source software, time banks and other forms of social relations.10 These "resources" are maintained for collective use and their defining relationship is one of collaborative care rather than private ownership.

Although original historical usage of the commons referred to the lands collectively managed by peasants for farming, foraging and grazing, the twentieth century saw its usage change linguistically, as it underwent a reconceptualisation to refer more broadly to anything not privately held. Today, the commons is often referred to as commoning to emphasise the process of engaging in the commons, or the practice of being in common.11 The prolific historian, Peter Linebaugh, popularised the term of commoning with his statement that: ‘There is no commons without commoning’.12 In other words, what constitutes the commons is not the resources alone, but rather the activation of those resources through community action and governance. David Bollier offers another succinct explanation:

There’s no single definition of the commons because it’s really more of a verb than a noun. It’s more of an activity of commoning — the social practices of coordinating and negotiating and resolving conflicts and punishing people who break the rules. And this takes place in a huge variety of different contexts. So it’s hard to say, “Here’s a 25 word description,” because any commons is so dependent on context. They are always evolving.

Artists regularly engage in commoning practices when organising creative collectives, producing group exhibitions, building shared studio spaces, and establishing galleries, journals, or political action groups, with various aims such as combating isolation, decreasing competition or fostering economic empowerment. Similarly, micro-utopias have manifested as small-scale prototypes for ‘do-it-ourselves’, offering experiences that bring an ethic of generosity, enjoyment and communalism. If well constructed, micro-utopias are spaces that people are attracted to, places that people want to visit, to live within, and to help create. Viewing West Space as a form of real-world, practical and useful micro-utopia, is worth serious contemplation as it makes visible the unique value of the small-scale, artist-led, experimental model, distinct from the general small-to-medium pool of arts organisations in Australia.

To better appreciate this unique value, it’s instructive to understand that West Space’s lineage goes back to the artist societies and collectives of the late 1930s and the conceptual galleries of the early 1970s such as Gallery A (est. 1959 in Melbourne and 1964 in Sydney), Central Street Space (est. 1964) and Inhibodress (est. 1971 in Sydney). However the writing and advocacy of West Space’s founding co-directors have articulated a uniquely Australian template for contemporary Artist-Run Initiatives linked to the stable and well-resourced model of Canada’s Artist-Run Centres (ARC). For example, West Space co-founder Brett Jones wrote on Canada’s ARCs in 2004:

ARCs in Canada are recognised as providing vital and essential opportunities for artists to be involved with exhibition, advocacy, networking and exchange opportunities. The participation of artists at various levels within an artist run organisation can be considered one of their nontransferable roles. These attitudes tie all artist run organisations together no matter whether they are large or small in their scale of operation. Artist run organisations are critical to the development, production and presentation of work as a kind of ecological system that is always in formation; before, during and after the exhibition. Art produces ideas for its maker, itself and its audience, but this process is continual, it never stops. This is an important praxis which recognises art as a series of social interactions that are in a constant state of realisation.13

Since the 1960s, artist-run centres (ARCs) in Canada have been resisting the dominating presence of American media culture and campaigning for artists' rights to choose how they make and present their work, leading to developments in policies on such progressive issues as payment of standard artist fees, anti-censorship, anti-racism and access.14 Today, we look to art-run and artist-run/led organisations to fulfil this same role within the Australian arts ecology without the concomitant bedrock of funding support enjoyed by their Canadian counterparts. The current reforms, conflicts and revisioning taking place across micro-scale arts organisations are reflective of a sector rapidly trying to cast off the outdated strictures of the Eurocentric artworld. The sector is also reorienting to embrace wider arts and non-arts audiences, recognise the vital importance of First Nations creative practice, and grapple with the ongoing violence of colonialism present within their creative programs, language and architecture.

The interaction between concepts of micro-utopia and the commons in this discussion of West Space allows for reflection on the holistic interpersonal, governance and bureaucratic life of an arts organisation, now in its 30th year. An appreciation for the active combination of these formal and informal factors is necessary to account for an organisation that was intentional from its outset and clear-sighted in its aim ‘to redress the characteristics of temporality, unsustainability and marginal existence foisted upon artist-run spaces at the time’.15 Reflecting on their intentions in 2005, Jones stated:

In fact, we had a clear vision that West Space was going to be a long-term proposition. If it were to affect change in the industry, the organisation had to become an entity in its own right, rather than an extension of our personal careers or personalities … I have always understood West Space as a professional service organisation. When it is able to work better and more effectively, it can in turn do more for artists. In a sense, West Space is a politically motivated organisation because through action and example it believes that artists can lead the industry in ways beyond their creative practice. Artists can represent the best interests of other artists and contemporary art though unique and professionally managed organisations; artists as professional managers is not a contradiction in terms.16

We can observe this founding ambition for West Space playing out in real time as this text is written. West Space remains an artist-centric organisation and, in 2023, has achieved multi-year state and federal funding, and now pays both its professional staff and exhibiting artists. They do this work from a posture that spans the down-to-earth operational rubric of an artist-run initiative with the organisational clout of a Contemporary Art Space.

The value produced by small-scale organisations of this type can be understood by considering the organisation’s founding aims and reflecting on the attempts by a relay-race of administrators and committees to achieve these aims through creative programming and bureaucratic reform over many years. This commitment to longevity and organisational maintenance maintains a site for Bourriaud’s sociability, Linebaugh’s commoning, and for the generation of what Sarah Thelwall describes as the phenomenon of ‘deferred value’, ‘whereby the value created by an initiating organisation is realised long after a commission has moved beyond its jurisdiction'. Thelwall emphasised this concept of deferred value within the research paper Size Matters (2011), commissioned by the advocacy group Common Practice which is dedicated to fostering the small-scale contemporary visual arts sector in London.

This idea of deferred value, micro-utopia and the commons positions us well to reflect on West Space’s recent Unison exhibition, which sets out to explore the organisation's 30-year legacy and build optimism for the future.

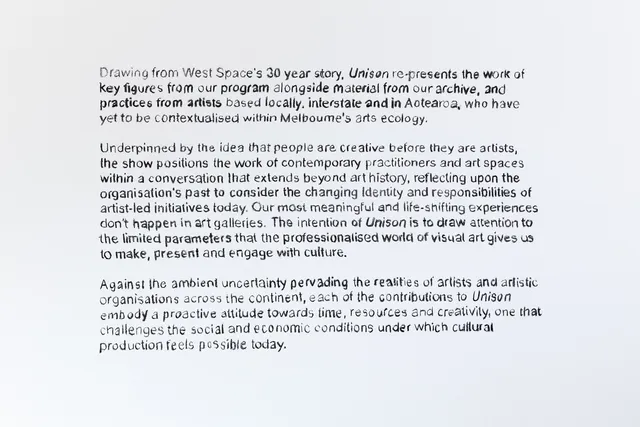

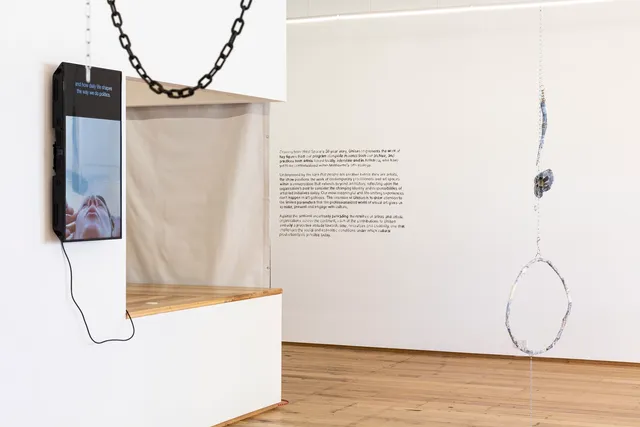

West Space holds a significant place in Australia’s art history as one of our longest-running artist-led galleries. For an anniversary exhibition, Unison was surprisingly light, optimistic, and forward-facing. Rather than an exhaustive historical survey, curator Sebastian Henry-Jones decided to select a small number of works to re-present in their new gallery space by key figures from their program archive alongside historical ephemera and collateral.

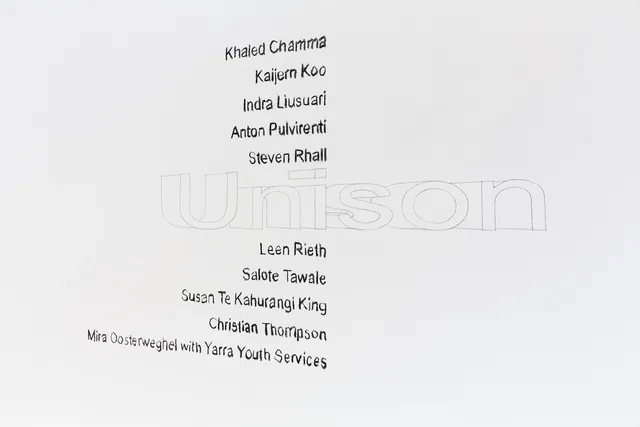

New vitality was injected via the selection of works by local and Aotearoa artists who were new to Melbourne's scene. Unison featured artists Khaled Chamma (Vic) Kaijern Koo (Vic), Indra Liusuari (Vic), Anton Pulvirenti (NSW), Steven Rhall (Vic), Leen Rieth (NSW), Salote Tawale (NSW), Susan Te Kahurangi King (NZ), Christian Thompson (Vic) and Mira Oosterweghel with Yarra Youth Services (Vic), along with a poster design by Alex Tanazefti. It is this combination of fresh faces and household names that gave Unison its potency as a proposal for the future.

Henry-Jones provided a playful, unpretentious and hopeful example of what a survey exhibition can be and his airy composition counteracted the enclosing that can happen in the historicising mode. Drawings, objects, photography, video and installation works cluster around the gallery space occupying floors, walls, and windows.

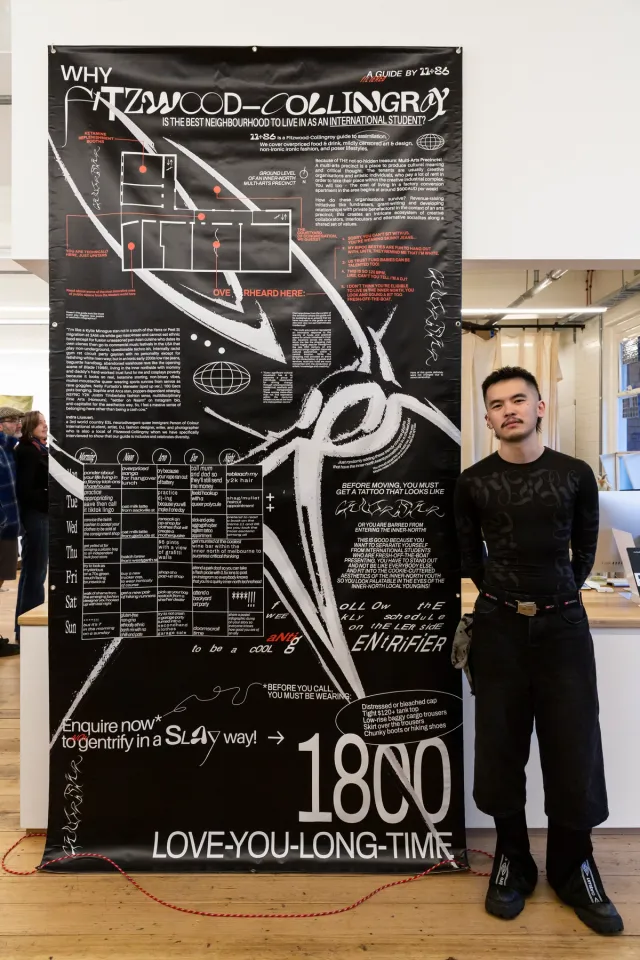

Audiences were welcomed into the gallery through a large floor-to-ceiling banner by Indra Liusuari that humorously asks, did you know there are art galleries in collingwood yards? (2023). Of course, humour is a critique, and Liusuari’s new work for Unison primes the visitor to think actively about the ethics of the artworld spaces they are entering and the gentrifying suburbs they often occupy. Markedly, the First Nations voices within the show deepen this critical engagement, questioning the restrictive nature of the Western-normative tradition of Modern art, the expectations imposed on the cultural production of First Nations people, and the sector’s all-too-slow move towards an appreciation for the complexity and power of First Nations cultures.

Henry-Jones’ framing document, On the Importance of Breaking Rules, provides us with the definitive guide on his methodology for artwork selection, the context within which he understands West Space to be operating, and the reforms necessary to meet the responsibilities of the future. However, the joy within this show is to be found in Henry-Jones’ invitation to the visitor to answer “How do we want to spend our time creatively today?”, and think more broadly about the capacity for authentic human creativity within and outside of the arts. There is genuine enjoyment evident in the playful and inclusive works on display and by inviting audiences and the art sector to consider who the exhibition is for, what publics West Space serves, and whose creativity is welcomed within the gallery. Unison interrogates what a survey exhibition should say about the past and what statement it should make about West Space’s intentions and responsibilities for the years to come.

Small-scale organisations like West Space have been built piece-by-piece over many decades by artists and artsworkers through the investment of vast amounts of voluntary labour and their own money. West Space is part of a rich continuum of practice where artists have challenged the sanctioned institutions of the time by creating their own opportunities for exhibition and dialogue. These collectivist strategies and collaborative actions, particularly those designed to take control of the means of production and agitate for change and recognition, are pivotal to the process of self-organisation.17 Although these practices are in themselves small-scale and hyper-local, they together give rise to networks of micro-commons and generative micro-utopias with greater potential to affect sector-wide change.

As an artist who spent my formative years studying and practising in the highly ephemeral Meanjin Brisbane scene, I was motivated by organisations like West Space to try and create lasting and well-managed artist-led organisations that would be useful and accessible to artists over the long term. The existence of West Space and other committed artist-led organisations is a powerful argument for artist-centric policy-making that reshapes the artworld.

West Space is an example of an ideal worth fighting for. Rally, regroup, rejuvenate, reform, reimagine, run to paradise!

Commissioned by West Space in response to Unison: 30 Years of West Space, 17 June → 12 Aug 2023. This essay has been generously supported by the Gordon Darling Foundation.

Channon Goodwin's work engages with collective, collaborative, and artist-run practice and forms of artist-led organisation building. From 2012-2021, Channon was the Director of Bus Projects, and is the current Director of Composite Moving Image Agency and Media Bank. In 2016 he contributed to founding All Conference, an organising network comprised of 17 artist-led, experimental and cross-disciplinary arts organisations from around Australia and is the current convener. Channon edited the book Permanent Recession: a Handbook on Art, Labour and Circumstance. Published through Onomatopee Projects, this book is an enquiry into the capitals and currencies of experimental, radical and artist-run initiatives in Australia and the labour conditions of working artists.