Sebastian Henry-Jones

“On the importance of breaking rules”

Unison is a group exhibition marking West Space’s 30th year. Underpinned by the idea that people are creative before they are artists, it looks to reflect upon the organisation’s past as a means by which to consider the identity and function of artist-run initiatives today, and their responsibilities to an ever-growing audience.

Since 1993, West Space has been responsible for presenting and contextualising local cultural production. As such, not only does our history present the evolution of an artist-led initiative, it also embodies broader shifts throughout the sector, detailing the nuanced ways that artistic production and discourse have evolved over the same period of time, within Naarm, and beyond, across so-called ‘Australia.’

In 2006 Christian Thompson presented a solo exhibition at West Space’s Anthony Street location in Melbourne’s Central Business District, titled Vote Yes – An Aboriginal Thompson Project. A subheading for the show rather scornfully read ‘vote yes to give Aboriginal people the right to make Contemporary art’. By re-creating an imaginary voting station in the gallery whereby (predominantly white) visitors could evaluate the contemporary value of cultural output made by living First Nations artists, Christian was challenging an established binary within the sector – existing along an historic, racialised prejudice – that understands the work of Aboriginal and First Nations artists as connected singularly to an un-evolving cultural tradition, belonging in museums as ‘artefacts’ rather than in spaces of contemporary art. While objects encountered in museums are often understood implicitly by audiences as belonging to cultures of the long-forgotten past, objects encountered in contemporary art galleries are read as current, ‘of the time’, and as such made by living, contemporary people.

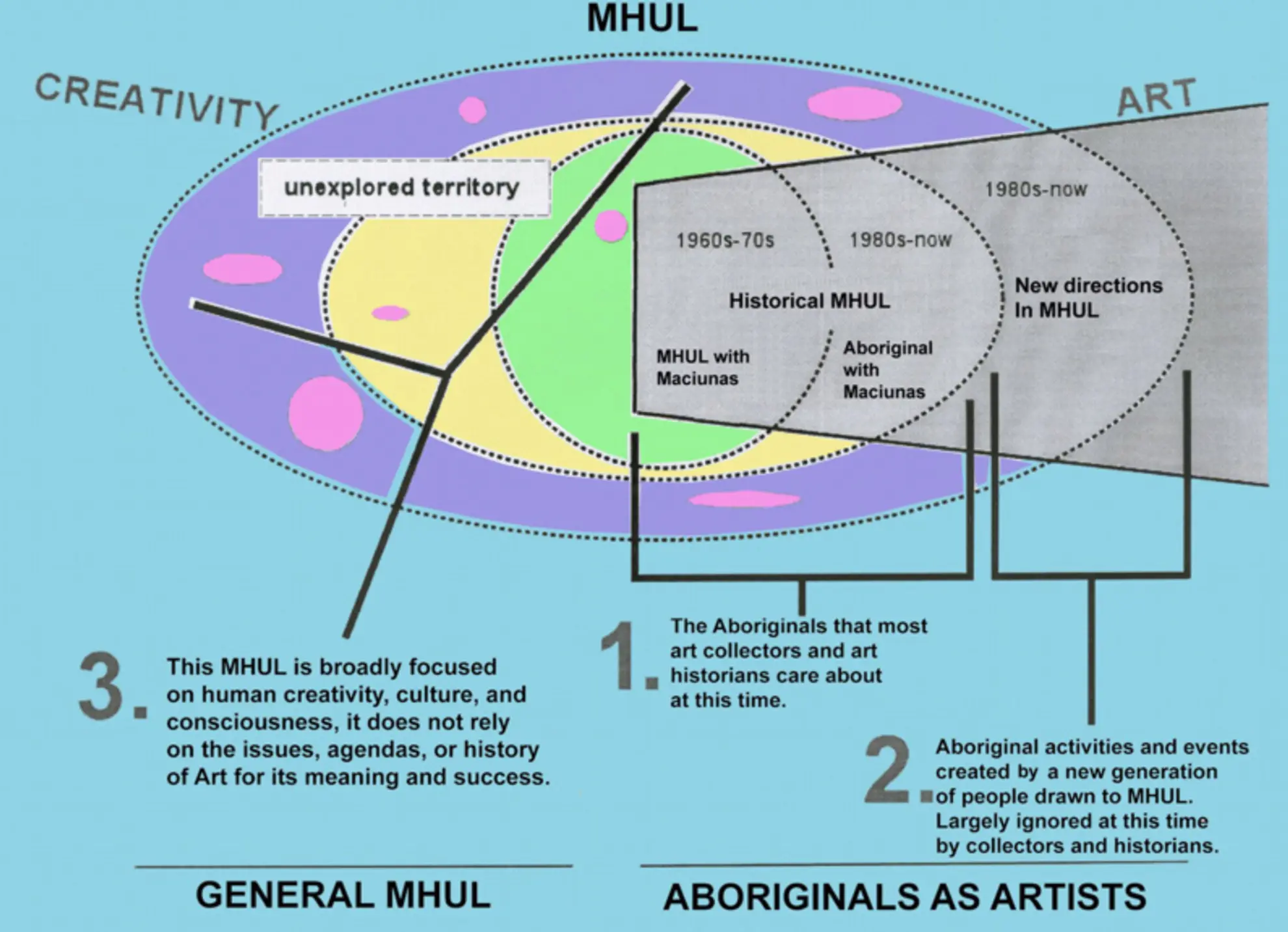

Within the show, Christian presented a diagram, printed simply on laminated A3 paper. The graph visually describes the narrow parameters available to any individual engaged in the field of visual art to make meaning. Taking the experiences of Aboriginal artists as its foundation, the graph depicts a conceptual map of the relationship between formal outputs of creativity, and the ways that these have been historically categorised and represented within institutional frameworks such as museums, universities and art spaces. Comparative to the vastness of any human’s capacity to be creative (represented in the graph by the entirety of the coloured circle), the Western-normative tradition of Modern art – rendered in grey – provides only a very small space within which groups and individuals may express themselves. With this diagram, Christian proposes a more fluid and interconnected approach to understanding and valuing art and knowledge, emphasising their diversity and interconnectedness rather than their isolation and categorisation.

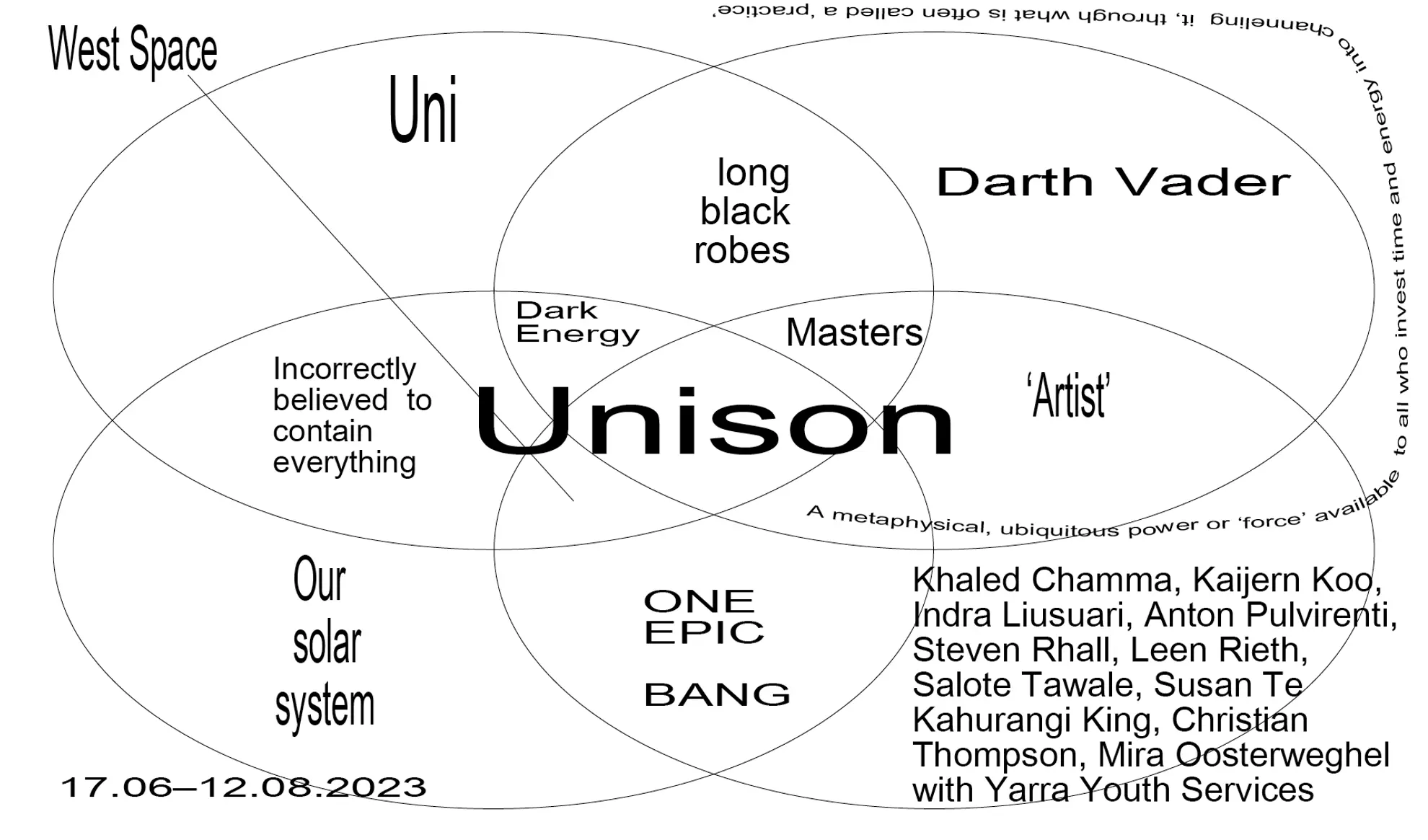

The hero image for this exhibition is inspired by Christian’s diagram. The four way Venn diagram is a relatively popular meme format that I was able to appropriate and refine with the help of graphic designer Alex Tanazefti. While its content humorously sketches out some of the ideas I wish to explore with the show, I also wanted to utilise the meme format itself: Memes constitute the most rapidly evolving and accessible form of visual culture available to us today, yet don’t find representation in any of our capital ‘I’ art Institutions across the world. Their exclusion is revealing of the blinkered, and more-often-than-not elitist understanding of culture that these places function by, as well as demonstrating the slow speeds at which institutions move at to keep up with culture.

The four circles of the Venn diagram bear a similarity to Salote Tawale’s large untitled paper mâché artwork in the exhibition, which she exhibited in her 2014 solo show at West Space’s Bourke Street location, titled Colonising West Space. The four, black and white triangular segments of the work come together in the centre, visually suggestive of a meeting place or vanishing point. In re-presenting the work of artists who have shown with the organisation in the past, it is my hope that we can think about the ways that West Space, and the sector itself, have or have not changed.

Steven Rhall’s 2021 exhibition with West Space at Collingwood Yards, Big Pharmakon, engaged with a similar territory to that laid out in Christian’s graph 15 years before it. To quote the statement written about the work, Big Pharmakon "unpacks inherited colonial powers and the ways they influence how First Nations people produce and present creative outcomes, and the ways these practices are located within artistic and museological histories."

Demonstrative of the influence of this relationship on the cultural output of First Nations artists is Steven’s Every 1’s a winger (Bingo Mode) – a flashing LED screen produced for a 2018 solo exhibition at C3 (now closed). To make the work, the artist visited a group exhibition at the Koori Heritage Trust, surveying the exhibition and the works within it through a Western lens, to record 51 typical responses to cultural material made by Aboriginal people working within the Australian arts industry. These include themes like ‘trauma’, ‘ethereality’, ‘togetherness’, ‘colonisation’, ‘hybridity’, etc. in its impersonal material form and the shallow diversity of its subject matter, the work is both ‘everything and nothing’ according to the artist. Every 1’s a winger (Bingo Mode) sketches out the varied expectations around outputs of cultural production made by Aboriginal people here, and the limited vocabulary we have to describe and understand the vast, interconnected nature of First Nations cultures. Within Unison, it hangs from the ceiling, pointing outwards through the gallery window to be observed in principle by construction workers engaged in the renovation of Melbourne Polytechnic.

I wanted to frame Unison with the idea that people are creative before they become artists because, as a young arts worker, none of the most meaningful cultural experiences I have had have occurred in an art gallery. I wanted to locate this idea within a lineage of artists and cultural producers in West Space’s own history, to show that it has been a concern of others over the years.

Christian Thompson’s other contribution to this exhibition is a huge photograph. In search of the international look was made two years before his West Space show, and is a recreation of an iconic self-portrait made by the even more iconic Tracey Moffatt. Similarly to the way that Christian has grounded his practice within the tradition of his artistic elders, it was also important to ground my ideas for this exhibition in the experiences and research of Aboriginal and First Nations artists. The incongruence between their cultures and their presentations in museums and galleries forms the foundation for this exhibition, which explores the professionalisation of artist-run initiatives, the gentrification of creativity and their influence on the cultural output and experiences of all artists living in urban centres today.

Alongside the three artists mentioned so far, in putting together the show I have been influenced by other events within West Space’s relatively long history. Mark Feary’s 2007 curated group exhibition Rules of Engagement, was a show that in his own words at the time ‘takes the artist as the central point of cultural production and then investigates the relationship between art or artist and the mechanisms of presentation, commerce, validation and exposure.’ The exhibition quite boldly took aim at the different structures, policies and powerbrokers with institutional authority that make up the art world, by presenting work that examined the often invisible exercises of power wielded by individuals and institutions, whose power is founded in the extraction of value from artists and their labour. One memorable contribution to the show included a banner made by Azlan McLennan, bearing the image of revered gallerist Anna Schwartz over which was emblazoned a quote from Karl Marx. In an interview about the exhibition with The Age, Mark speaks of the importance of artist-run initiatives, saying, "Artist-run initiatives such as West Space are integral to the contemporary arts industry in Australia, as they provide a platform which is ultimately geared towards the artist rather than the institution, or the audience for that institution." He goes on to detail the value of spaces like West Space, for their capacity to support risky and experimental projects such as his.

In 2023, West Space turns 30 years old, and as such is about to exit its Saturn Returns. The organisation’s longevity is often communicated as unusual amongst artist-run initiatives. However, there are many others in this city which have operated for similar lengths of time. This year, KINGS artist run turns 20. BLINDSIDE is 19 years old. Bus Projects is 22, while TCB is 25. SEVENTH Gallery is 23 years old in 2023, while larger organisations ACCA and Gertrude Contemporary turn 40. The similar age of these artist-run initiatives points to a different funding climate before the turn of the century in Victoria but also Australia more broadly, one in which art and culture were wholeheartedly supported by state policy. Most of these spaces occupied locations much more central to Melbourne’s CBD. In recent years, KINGS has relocated to the Western outskirts of the CBD to its new home near Victoria Market. TCB moved North to Brunswick. SEVENTH and Gertrude Contemporary both left Gertrude Street for new locations in Richmond and Preston respectively. BLINDSIDE remains in the CBD in the Nicholas building, the site of a brutal rent increase in the last year or so that has cast the future of the building’s numerous creative tenants in doubt. These movements are responses to the increase of rent – felt deeply by art galleries and small businesses in urban areas across the continent. In 2020, West Space moved from its iconic location on Bourke Street in the CBD to Collingwood, taking up its place – along with Bus Projects – as a tenant in multi-arts precinct Collingwood Yards.

A multi-arts precinct is designed to place its tenants – creative organisations and artistic individuals – in collaboration with each other, to produce cultural meaning and critical thought. Within this, the work of less financially viable not-for-profits is offset by revenue-raising initiatives, bringing together an intricate ecosystem of creative collaborators along a relatively uniform, shared set of values. Much like the shopping mall made hugely popular throughout the late 20th century, an arts precinct brings together disparate cultural experiences within a central location. While the shopping mall provided an arena for the consumption of goods and services, multi-arts hubs are more concerned with the production of artistic knowledge, creative expression and culture. The multi-arts precinct constitutes a very particular response to our current economic and cultural climate, with the announcement of another one in Richmond Power Station at Cremorne (funded by Naomi Milgrom) as well as the announcement of an Arts Precinct in Kingston, a suburb described by locals as the ‘Paris end’ of Canberra. Today, it is not too hard to imagine multi-arts precincts popping up in numbers everywhere across Australia.

The buildings that constitute Collingwood Yards were built 140 years ago, housing a technical school, a courthouse and then council chambers. The drastic evolution in the way these buildings have been used throughout time embodies the rapid transformation of Fitzroy/Collingwood itself, which in recent years, has undergone immense changes in the gentrification of its social and economic fabric. Improvements was West Space’s inaugural exhibition at Collingwood Yards, curated by the Director at the time Amelia Wallin during the early years of Melbourne’s COVID-induced lockdowns. The exhibition existed in tandem with Reproductions, a show initiated by 1856 at the Victorian Trades Hall. Taken together, the two shows investigated the conditions under which art is produced. They asked the question: “what reproduces the conditions for an artist’s work?”, listing several factors like cultural relationships and identities, state policies, economic and social determinations, class privilege, colonisation, habits of seeing, perceiving and producing. I am interested in thinking about how all of these interact at the site of gentrification, that being the displacement of diverse, lower-income people in an area, and their replacement with more affluent residents and businesses.

Not only does Collingwood Yards embody the inevitable gentrification occurring throughout inner-city suburbs in the North of Melbourne – it has undoubtedly been the dominant force in the meta-narratives of Melbourne’s artist-run initiatives and their recent relocations. As a homogenising force, what kinds of conditions do areas under intense gentrification create for the production of art and culture, for young, emerging artists and their communities, situated as they are around and between local artist-run initiatives? Or as put by the curators of Improvements & Reproductions, “what is the ability of the work of art to reflect the conditions in which it is made… what does it reproduce?”

Under gentrification, emerging artists are faced with a conformity of aesthetics and values in their neighbourhoods. Conventional, middle and upper class behaviour becomes a requirement for surviving socially, developing professionally, and earning a living. This alters the goals and aspirations of emerging artists, as it becomes of the utmost importance for those with relatively less power in the arts to mirror the interests of large institutions to survive. We are at an interesting point in human history, whereby we are all called to differentiate ourselves from the crowd as much as possible. All the while, the environments we exist in, the educations we receive, our cultural influences, the technologies and forums available to us in which to express ourselves are becoming increasingly standardised, increasingly corporate, increasingly homogenous. As such, the gentrified urban context has an enormous effect on the subjectivities of cultural practitioners, particularly those that are emerging.

This is the territory explored by Indra Liusuari’s sardonic banner work, did you know there are art galleries in collingwood yards?, which ironically observes the relatively predictable typologies of cultural expression in urban cultural centres deemed ‘safe’ by white, bourgeois standards. As creative people, we are forced to choose between a limited variety of products, opinions, ideas and cultural markers with which to identify ourselves as individuals. What does it mean then to bring multiple artistic initiatives together in the one place, to compete for the few funding opportunities available with little way of differentiating themselves and the context they work within from one another? As one colleague said to me in 2021, “it’s like they put all the arts organisations in one place and turned the funding down”. This is an important conversation for every cultural organisation located in an urban context to be having, not only internally – but even more importantly – with a cultural organisation’s neighbours.

Thinking carefully – the kinds of social behaviour and attitudes towards money that are necessary to be able to pay contemporary real estate prices, are encompassed by professionalisation. Over its 30 year story, West Space has followed along this trajectory. When the organisation began, the artists running it volunteered their labour, almost exclusively showing the work of artists from within their community to an audience made up of that same community. Today, West Space pays a part-time curator (me) to support the creative projects of artists based all over Australia, to a similarly dispersed, ever-growing audience of largely university-educated, artistically-inclined and ‘progressive’ individuals. The rising cost of living, the changing funding landscape (cowabunga), the lack of job opportunities for arts workers and the astonishingly low number of opportunities for emerging artists across the sector, has seen the rapid professionalisation of our industry over the last forty or so years. This is in line with a process set in motion within our universities in the 80s, catalysed by neoliberal cuts to State funding for higher education. Whereas public funding for universities constituted roughly ninety percent of universities’ total funding in the late '80s, today that figure has dropped to around forty percent. As a result, Universities in Australia have moved to a profit-seeking model resembling those of corporate businesses, something which can also be observed in larger institutions in the visual arts, and to a much lesser (but noticeable) extent in the ARI sector. There is not enough room for it here – but there is also an interesting discussion to be had about the ways that Universities are gentrifying our cities across Australia, through property speculation, and partnerships with student accommodation corporations, which support Australian universities and their huge reliance on international students.

The nationwide trend over the last decade – exacerbated by pandemic – that has seen Universities discontinue hundreds of subjects, courses and the academic staff who teach them, is one means by which Universities are streamlining their businesses along financial lines. The cutting of predominantly technical, creative subjects like fine arts allow Universities to prioritise subjects that connect more directly to employability outcomes. Almost all artists and arts professionals who show and work in artist-run initiatives across Melbourne have an undergraduate or postgraduate degree. The homogeneity of the process by which young artists and arts workers prepare for professional lives in the industry, combined with the lack of opportunities for those not institutionally produced, results in an Australian visual arts scene that is complicit with and a tool of the colonial state – which is the opposite of what it should be if art truly is a tool of social transformation. Showing in artist-run initiatives, recent graduates become focussed on a kind of mainstream success predicated on the repetition of established truths. This ignores critical thinking in favour of what is already known.

Kaijern Koo’s contributions to this exhibition are demonstrative of the limited ways that young arts workers feel like they need to present themselves in professionalised art spaces today. One side of her sculptures are rendered in clinical, machine-cut marble, the other covered in soft fabric much like a plush toy. They sit on the window sill, so that the former side faces into the gallery, the latter only viewable by audience members who remove themselves from within West Space.

The notion that everyone is creative but that the category of ‘artist’ best describes a situation in which a creative person looks to make a career, calls us to re-frame our relationship to fine art under the conditions caused by professionalisation and gentrification. If creativity is a particular practice of living inherent within us all, it follows that art-making and the people who do it exist with or without institutional validation and permission, before funding applications, cultural policies and capital. This isn’t to say that people shouldn’t be remunerated for their creative labour. Neither is it a rejection of the nurturing structures and relationships that an industry can provide to those looking to pursue careers as artists. One of the aims of Unison is to reconsider prevailing attitudes towards the social and economic conditions under which cultural production feels possible today, and in doing so, to challenge the kinds of cultural output that such conditions encourage.

The absence of strong, consistent State or private support for art has been a perpetual condition in Australia, within which material constraints become the context in which culture comes into being. I wanted to include the work of legendary artist Susan Te Kahurangi King in this exhibition. Susan is a self-taught artist who insisted on making art every day for years before her discovery. In the materials she uses, her way of working and her disregard for the demands of the market or the academy on her work, she embodies an attitude to art-making that is resourceful and self-sustaining, that is not bound by the conditions under which it occurs.

From his Melbourne home, for years Khaled Chamma has made idiosyncratic drawings at nearly the same voracious rate as Susan. While he has not shown in this city’s artist-run network before, this year Khaled participated in the ‘Outsider Art Fair’ in New York. Some of his pieces were collected by KAWS, an individual who happens to also be the biggest collector of Susan Te Kahurangi King in the world.

I believe Susan’s beautiful, at times dark drawings to be engaging to both those who have studied art and those who haven’t. I have the same feeling about the work of Anton Pulvirenti, who lives on the Central Coast of New South Wales. Anton specialises in chalk, mural drawing on the street, enjoying success here and overseas as one of Australia’s most decorated chalk mural artists. However, his work has almost never been included within spaces of contemporary art, even though chalk drawing itself constitutes an art historical tradition dating back to 15th century Italy. I wanted to include Anton in the show to elevate the art form. And anyway, his work is engaging to a far broader spectrum of people than most examples of contemporary or conceptual art.

Relative to the long length of time she has been making art, Susan Te Kahurangi King has only enjoyed institutional recognition recently. Her story calls us to ask questions of the established category of ‘emerging’, a category that all the artist-run initiatives mentioned in this essay centre their work on. The category of ‘emerging artist’ is more nuanced than an exhibition comprised of such individuals can account for. Which is to say, the artist’s path is always different. Some might take years to ‘emerge’, some might re-emerge after taking a break…some might re-re-emerge. Twice, three times over. Some might never emerge, yet live long artistic lives with creativity at the centre. By including work made by young people from the Youth Centre in collaboration with local artist Mira Oosterwheghel, I hope that one group of people who haven’t had a formal arts education (yet) feel like they belong in places like West Space.

Here I would like to list the objectives that I made for myself in the development and curation of this exhibition. It has felt like a big responsibility to work on something that celebrates the history of such a loved artistic organisation, and as such, a list feels like a good way of communicating my intentions. Fitting for a project with the title Unison, there have been many, seemingly disparate threads and moments to draw together in one exhibition space.

→ To re-present the work of artists from West Space’s past, as a means of thinking about how the organisation has changed over time.

→ To challenge historical notions of high art vs low art, as well as who can present art in the ever-professionalising small-to-medium sector.

→ To show the work of an emerging group of artists alongside their more experienced peers.

→ To support as many artists as possible with a paid, professional opportunity.

→ To work resourcefully.

→ To reflect on the idea of what an ARI should be today.

→ To articulate West Space’s current context in Collingwood and in the broader arts ecology.

→ To make an exhibition that is fun, welcoming and engaging to both those who have been educated about art and those who haven’t.

Sebastian Henry-Jones is the Curator at West Space. His curatorial approach is led by an interest in DIY thinking, and situated in the context provided by the gentrification of Sydney and Melbourne’s cultural landscapes.

Related

“Unison”

Khaled Chamma, Kaijern Koo, Indra Liusuari, Anton Pulvirenti, Steven Rhall, Leen Rieth, Salote Tawale, Susan Te Kahurangi King, Christian Thompson, Mira Oosterweghel and Sebastian Henry-Jones

17 June → 12 Aug 2023