Joanna Kitto

“On storytelling and subversion”

“Life is a tangled web of unexpected events. Never claim or believe that anything is certain.”1

Stranger than fiction brings together eight artists troubling the boundaries between reality and fiction. Across film, sculpture, text, printmaking and performance, they reckon with the impossible challenge of representing a singular way of portraying the world or existing within it, and the absurdity in trying.

Archie Barry, Teresa Busuttil, Nicholas Currie, Andrea Illés, Rosie Isaac, Basim Magdy, Rä di Martino, and Sammaneh Pourshafighi engage in material and narrative experiments in an attempt to pin down, tease out or upend the ever elusive ‘truth’ of the matter.

Their works are satirical, questioning, thoughtful, and at times, they are funny. In a moment when the fear of artificial intelligence’s deception reverberates through the mainstream, we remember artists are the masters of this domain. They understand the power of embellishment and augmentation to (re)imagine and (re)write histories from underrepresented perspectives. Artists remind us of the many realities we each occupy, no two ever the same.

This essay is one version of the overlapping themes in Stranger than fiction; traversing the slippery, subjective nature of perception and the fabrication(s) of time, language, class, memory, place, and the self.

Inspired by her background in theatre, Rome based artist Rä di Martino has been interested in the slippage between the real and the unreal for over two decades. Sets, actors and props are used to pick apart human relationships, cinematographic traditions, the theatre of war, and the fabrication of history.

I first came across her practice through the photographic series No More Stars (Star Wars), 2010. Rä travelled to the deserts of Tunisia to photograph the Star Wars film sets, left abandoned when the production ran out of funds (or didn’t prioritise leaving the desert as they found it). No More Stars depicts the decaying, sand-swept dome of Luke Skywalker's Tatooine home; flanked by dunes, the ruins of a circular, industrial structure lying crumbling before it, partially submerged beneath the sand. The images have a dreamy, cinematic quality while taking a jab at the waste wrought by colonialism, capitalist consumption, and environmental apathy. Speaking on the work, Chiara Bertola writes, “as the language of art often succeeds in doing, with ready-made images revealing an underlying truth, Rä di Martino emphases the arrogance of those who believed they had the right to colonise far-off foreign lands, leaving their rubbish behind.”2

At West Space, Rä’s epic two-channel work Afterall (A Space Mambo), 2019, takes place in another deserted landscape, this time an imagined one in an unspecified space, suspended within an indefinite time. The sky is without atmosphere. The landscape inhabited by the only survivors of an unknown environmental disaster. Throwing off language, individuals and small communities find common ground in humming as a form of communication.

I see Italian author Italo Calvino in her approach, whose short stories Cosmicomics, 1965, took scientific facts such as tidal acceleration or the Big Bang, as a jumping off point to explore complex themes from interpersonal relationships, the anthropocene and postmodern theory. You can only truly experiment with something you have a handle on, and is this interest in grasp - and stretch - of the truth that Stranger than fiction is interested in.

A sentiment that recurs throughout Rä’s practice is a fear of a future that cannot be seen. This fear prompts the characters in her work to find refuge in an imaginary world from the past. Familiar objects, images and sounds are the symbols by which the characters in Afterall identify themselves. In the distance, a radio crackles … I'd Like to Buy the World a Coke…. a sonic reminder of that 1970’s optimism for technology’s social potential that echoes through the landscape.

Temporal remixes run through the work of Egyptian artist Basim Magdy. Now based in Basel, Switzerland, Basim has been making images for two and a half decades, beginning with painting, before expanding his practice to include photography and film. Like Rä di Martino, much of Basim’s work looks at the present moment as if looking back at history from the future.

Basim’s films are satirical, surreal, and existential, prompting a re-evaluation of human ambition and utopian aspiration in light of (post)modern and (post)colonial realities. They have a dreamlike quality, where familiar elements populate unreal landscapes and the past, present and future coexist in one plane. These are both material and narrative choices. Textured, analogue film leaves traces of decay while at the same time are intensely vibrant, echoing the colours of pop-culture imagery.

In 13 Essential Rules for Understanding the World, 2011, a list of guidelines are narrated by tulips. It’s a humorous and affective perspective on the complexities of the human condition, that seems to have only grown in relevance in the thirteen years since its creation. 13 Essential Rules is prescient in its depiction of social media and internet culture when faced with self improvement, dry existentialism, absurdism, death and war within one scroll. It parodies and subverts the instructional film format, informing us that inaction may be the most effective way of being under the conditions of existence shaped by colonial legacies, corrupt governments and late stage capitalism.

“Never forget there are almost 7 billion other people here. You don’t matter. Really, no one cares!”

Reckoning with death becomes the focal point in Basim’s FEARDEATHLOVEDEATH, 2022. As an immersive, hallucinatory dreamscape, the film muses on the absurdity of death and dying without first trying to understand it. Taking cues from science fiction, horror and nature documentaries, the work takes place within a universe of sounds and images that suggests a present moment suspended between a mythic past and uncertain future.

Art created with psychedelic connections can produce drama against the silence of normative existence. As images alone cannot hold the porosity of the inner/dream world, what is unable to be experienced directly can only be reached as events are (re)read and (re)told. There is something utopian in what psychedelia can offer.

Like Basim Magdy, Nicholas Currie’s emerging practice started with painting and is evolving through experimentation. Standing strong in the centre of Stranger than fiction is Spot the difference (door), 2024. A descendent of the Mununjali clan of Yugambeh people, Nicholas grew up on Larrakia Country before moving to Wurundjeri Country, where he went to art school. The invitation to be part of this exhibition prompted Nicholas to experiment with materiality and storytelling through sculptural installation. He has created a door adorned with painting, a (lucky) horseshoe, and personal artefacts; a pair of thongs, a shirt, a cap. The artist is present, and absent. A candle burns down, marking the passing of time.

Nicholas tells me his family sardonically poking fun at the idea of Australia as ‘the lucky country’. Cartoon-like in the looseness of its creation and the precision of its wit, Spot the difference (door) upturns the perception of so-called ‘Australia’ as a place of freedom and abundance, a reminder that our experience of the world is through the lens of our privilege.

Humour is the great equaliser. Comedy, while not the opposite of seriousness, can provide a welcome relief and an antidote to an (art) world that can take itself too seriously. Used wisely, humour can ridicule the status quo, dismantle flimsy concepts, and illuminate the absurdity of the everyday. It can cut to the chase, revealing many of the complexities and layers of meaning that contemporary art (and the discourse around it) hopes to address. And when our reality is seriously challenged, a common reflex is to laugh, dispelling nervous energy as we recalibrate. Funny deserves to be taken seriously.

Another artist precise in her use of wit is Teresa Busuttil. Teresa’s sculptural and filmic practice investigates personal and familial history, the Maltese diaspora, archives and shared pools of memory. Charismatic Inflation II, 2021, explores the narrative possibilities of embellishment. Teresa understands that when we tell stories, facts and sequences are often exaggerated, twisted over time by emotion, experience, positionality and intent.

Charismatic Inflation II takes as its starting point, audio from a dramatised reenactment documentary depicting an iconic Australian fear — being attacked by a shark. The short film shifts focus away from the strict accuracy of facts to emphasise the possibilities unlocked by imagination and exaggeration, highlighting the way narratives can be reshaped and enriched through creative reinterpretation.

First published in online film series The One Minutes, Charismatic Inflation II was also shown in the 2021 Kinemastik International Short Film Festival in Malta.

The connection with Malta runs deep. Teresa’s late father was born on the Mediterranean island before migrating to South Australia by boat as a young man, living his adult life as a diver and fisherman. The ocean is a potent metaphor for Teresa, holding notions around intergenerational memory and cyclical time, with the repetition of the tides the force holding these ideas together. An invitation to participate in the Malta Biennale in early 2024 prompted Teresa to spend the first months of the year on the island to prepare her work. At the time of writing, she hasn’t left. The Biennale’s theme Can You Sea?: The Mediterranean as a political body allowed for further consideration around the ebbs and flows of life surrounded by water, exchange, history and time. Also showing in Stranger than fiction is a new work made during this time.

time poor dream pool, 2024, is a puzzle of 1950s Malta, embalmed in crisp blue resin and embellished with swimming pool tiles. Amid the pace of modernisation, gentrification and environmental crisis, Teresa freezes memory in a material reminiscent of the one constant encircling Malta; the Mediterranean sea. The once treasured object — now frozen in time — reflects the challenge of trying to maintain a static understanding of a rapidly changing world. Basim’s words come to mind, “with every purchase or exchange, you drown faster in absurdity whirlpools.”3

The pool tiles are a reminder of the trend for turning once charming, historic spaces into Airbnbs, commercial hotels and tourism hot spots, ultimately sacrificing a slower, more authentic, traditional way of life for profit. Staring into the pool, I think about what is lost and what remains, and the debris of the past that haunt our future.

“I’m not the first person to realise how intimately waste is tied to property. A thought passes across my mind, I don’t know whether to hold onto it or let go, it is this – the moment that a thing becomes waste shifts on the axis owned or not. There is a desperation to the act of discard, as if by throwing away the material things it becomes possible to expunge whatever emotional, ecological, political or other consequences of the thing in the world. It would be easy to list a series of these corporate and colonial disavowals.” — Rosie Isaac4

Suspended across the windows of West Space, looking out onto the rapidly gentrifying suburb of Collingwood, Rosie Isaac returns a horizon line to view. The dip-dyed paper in Tip test, 2024, has been meticulously created through a process over many months, sparked by the phenomenon of fasciation (abnormal plant growth) that occurs in the natural world as witnessed in the sheoaks in Darebin Parklands (just north of Collingwood). Fasciation occurs during genetic mutation, infection, or when hormonal imbalances in the plant’s growth cells cause tissue to become elongated perpendicularly to the direction of growth. Google fasciation and you find a daisy with a yellow centre that is less a circle and more curved ellipse, “like a broken egg yolk running with gravity, a new dimension for the flower” that supposedly occurred after the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Here on Wurundjeri Country, it is speculated that the sheoaks have become fasciated due to refuse dumped in the quarry that has leaked into the waterways, throwing off the hormonal balance of the trees. Whereas their leaves are typically fine, stem-like needles, these sheoaks have flat, spiralling leaves. Through conversations with a local park ranger, Pete, Rosie discovered that in the mix of dumped refuse, chromium has leaked from chrome hubcaps, fenders, headlamps and door handles into the soil and, over time, the sheoaks.

Rosie’s work, as it often does, began with language. In this case, she has developed a performance lecture for the Stranger than fiction Symposium. (Author's note added August 2025: elsewhere on Offsite, you can watch documentation of the lecture by Ahmed Coshnow, and read an experimental response by Debris Facility).

While writing, Rosie undertook a process to produce a ‘litmus dye’, using litmus powder and cabbage, substances that change colour in response to pH levels. She then dyed the paper in this mixture before dipping it in leachate ponds in the parklands. In some cases, algae bloom from the surface of the pond was picked up when the paper was dipped. Rosie’s research included pH readings from the chemistry reports on the water quality, meaning she was free to experiment with the way she dyed the paper, using an interpretation of a scientific ‘test’ process. Rosie creates a horizon line to mimic the litmus test, a powerful symbol of individual and collective thresholds of belief and scientific ideas of truth.

When looking up, we discover hubcaps arranged in a play on the bonds that form chromium molecules. Total dissolved solids, 2024, is held together by magnets, as chemical bonds bind molecules, creating temporary connections that are essential to life. Rosie points out that the word chromium has roots in the Greek word for colour, “the colour of all colours reflected”.5 Seen from below, the work forms a series of convex mirrors, eye-like, watching.

Paper meets water meets illusion elsewhere in Stranger than fiction. Tehran born, Naam/Melbourne based artist Sammaneh Pourshafighi’s psychedelic monoprints are made using Ebru water marbling, a technique with historical roots across many cultures from Türkiye, Iran and SWANA regions. Ōmukade and Porphyion form part of Sammaneh’s ongoing series of material experiments All The Devils Are Here, manifesting devils, demons and djinn inspired by Persian mythology and Islamic demonology.

The longer we gaze, the more swirls into view. The ink and the artists’ hand work together to create unruly visions reminiscent of hallucinations, the sensory experience created by the mind that can appear entirely real when left unchallenged by science or reason. There is of course a long history of cultural use with mind-altering substances to conjure an understanding of what might lie beyond what the naked eye has the ability to perceive.

As we spend longer in the gallery, Archie Barry beckons to us through voice. Archie's research and practice is concerned with (re)configuring a trans conception of time and the future. Their time-based practice is process-oriented, embodied, and performed. Over the last decade, Archie has cultivated a genealogy of personas based on personal experiences of power, loss and mortality, producing self-portraiture that challenges dominant notions of personhood as stable, sequential and legible. In their current research, Archie is considering the relationships between practices of ego dissolution (meditation, parapsychology, drug use) and the neoliberal ideologies of liberation that came into prominence in the 1970s.

Archie has been researching archival ephemera in early trans justice organisations at the Transgender Archives in British Columbia, Canada. When they return to Wurundjeri Country, this work materialised in full.

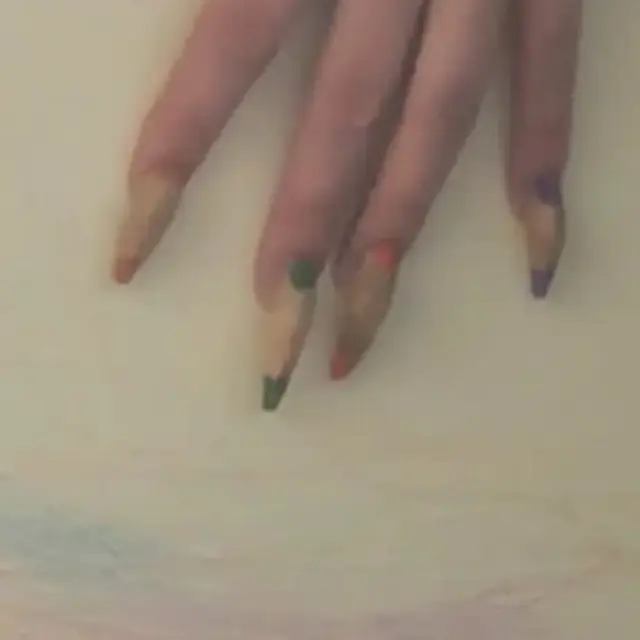

Wall drawing (I know you are out there somewhere), brings language to the gallery through lyrical hand movements, their hands adorned in fingernails fabricated from multicoloured pencils that make marks, gestures with all five fingers translated to the written word. This iteration of Archie's ongoing research around the trans ontology of disembodiment, perceptions and sensations of being out-of-body references the life and writing of Reed Erickson, an eccentric and troubling figure in the history of trans organising.

Archie's embodied mark making and language materialised on the wall, charged with their hum. Archie sang in harmony with themselves, as their fingers traced the wall, playing it like an instrument. Before and after this moment, Archie’s presence is held by a deep hum emanating from within the gallery walls. Gently reverberating at the height of Archie’s mouth, the artist recorded their voice by singing directly into a hollow plasterboard wall, with a microphone positioned in the next room.

Questions that have informed the development6 of Stranger than fiction have been: beyond (often unsatisfactory) devices such as video or photographic documentation, how do we hold the presence of an artist who uses their body within the timeframe of an exhibition?

How do we honour practice where bodily transmission and translation are a central tool, the matter in question, or both?

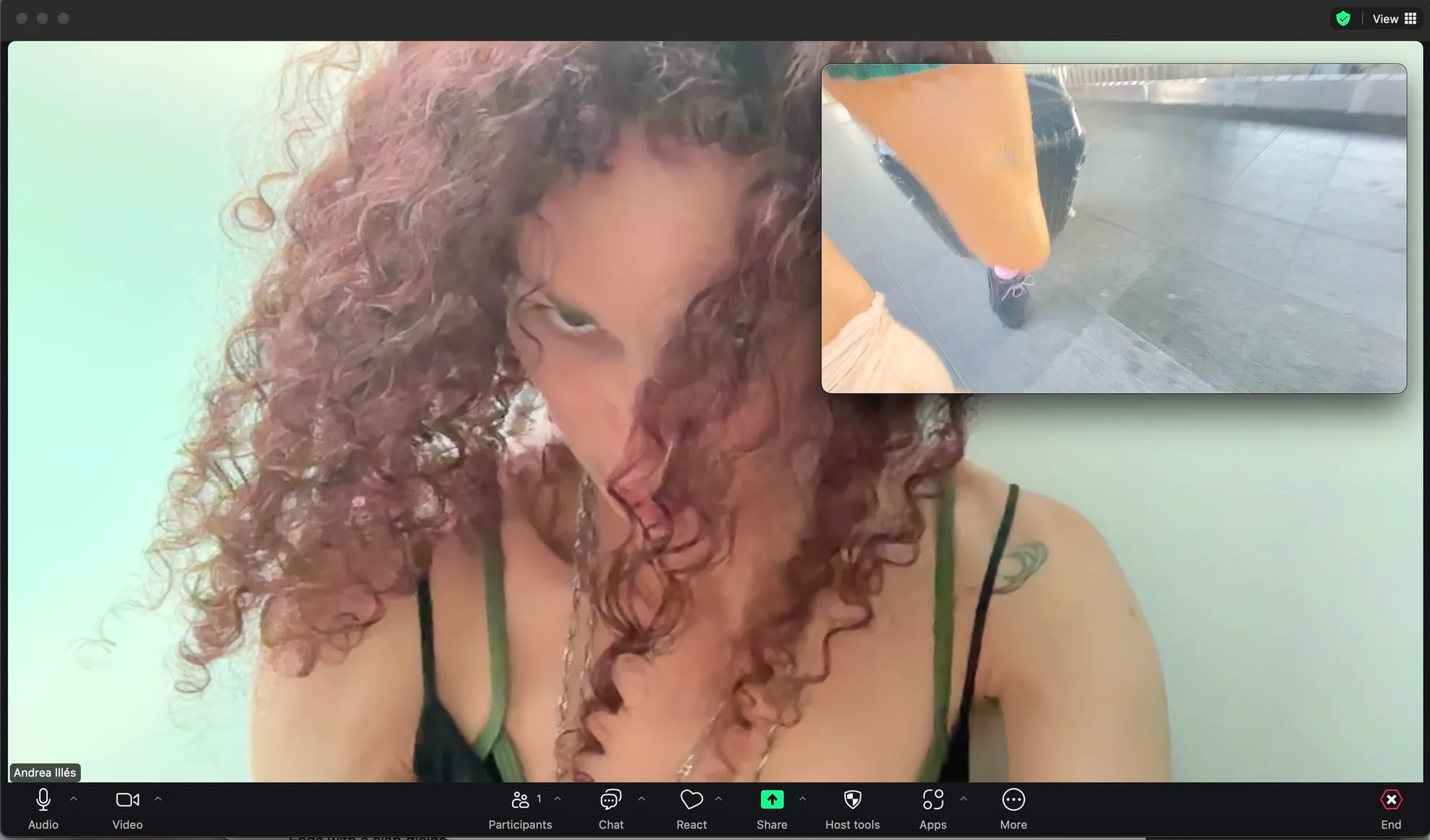

These are ongoing concerns for Andrea Illés. With sorry I was so hungry, she plays with absence and presence with a project in multiple parts. For the first month of the exhibition, Andrea is represented by a video connection between the gallery and her West Space Studio. At West Space, the stage is set on a humble computer screen, sitting on the threshold between the office and the gallery. We anticipate her stepping into view at any moment.

This work is activated by a durational livestream performance grappling with the Sisyphean task of image-making as true representation of the self. The artist occupies her studio, making images with her body, viewable both in-person and transcribed by screens, in the gallery, or our personal devices. You decide how you wish to view Andrea's transcription.

Many of the artists in Stranger than fiction have taken the opportunity to experiment and exist in the fertile space of the unknown. This fluid, generative space allows for multiple, overlapping realities to co-exist simultaneously.

This is a reminder (sometimes we need one) that our relationships to place, memory, history and one another are viewed through the lens of our own frame of reference. My normality is your absurdity etc. There is no one reality, how can there be, when there are "7 billion other people here".7 This is where empathy is seeded, and creativity flourishes.

I'd like to thank all the artists, Archie Barry, Teresa Busuttil, Nicholas Currie, Andrea Illés, Rosie Isaac, Basim Magdy, Rä di Martino, and Sammaneh Pourshafighi, for your compelling ways of working and communicating. Thank you Zamara Zamara and Anatol Pitt for installation wizardry and support, Bala Starr for our many generative conversations, and Helen Grogan, for bringing magical ways of conceptualising, choreographing and caring for the Stranger than fiction Symposium and evolutive program.

Joanna Kitto is an arts worker focused on refining her inclusive, personable and receptive approach to the presentation of contemporary art. She is currently the Director of West Space. In 2014, Joanna co-founded fine print, an independent platform cultivating experimental and critical discourse online and in public spaces.

Related

“Stranger than fiction”

Archie Barry, Teresa Busuttil, Nicholas Currie, Andrea Illés, Rosie Isaac, Basim Magdy, Rä di Martino, Sammaneh Pourshafighi and Joanna Kitto

29 June → 31 Aug 2024

“sorry I was so hungry”

Andrea Illés

9 Aug → 31 Aug 2024