Sophia Cai

“#CASUALFAN, an Introduction to Sincerely Yours”

Dear Min Yoongi,

How are you? Have you eaten? Are you well rested and recovered?

I was so worried when you returned from America last month and tested positive, but I’m glad to hear you are now out of isolation. I hope you get to spend the new year with your family and closest friends, please give Min Holly a hug from me.

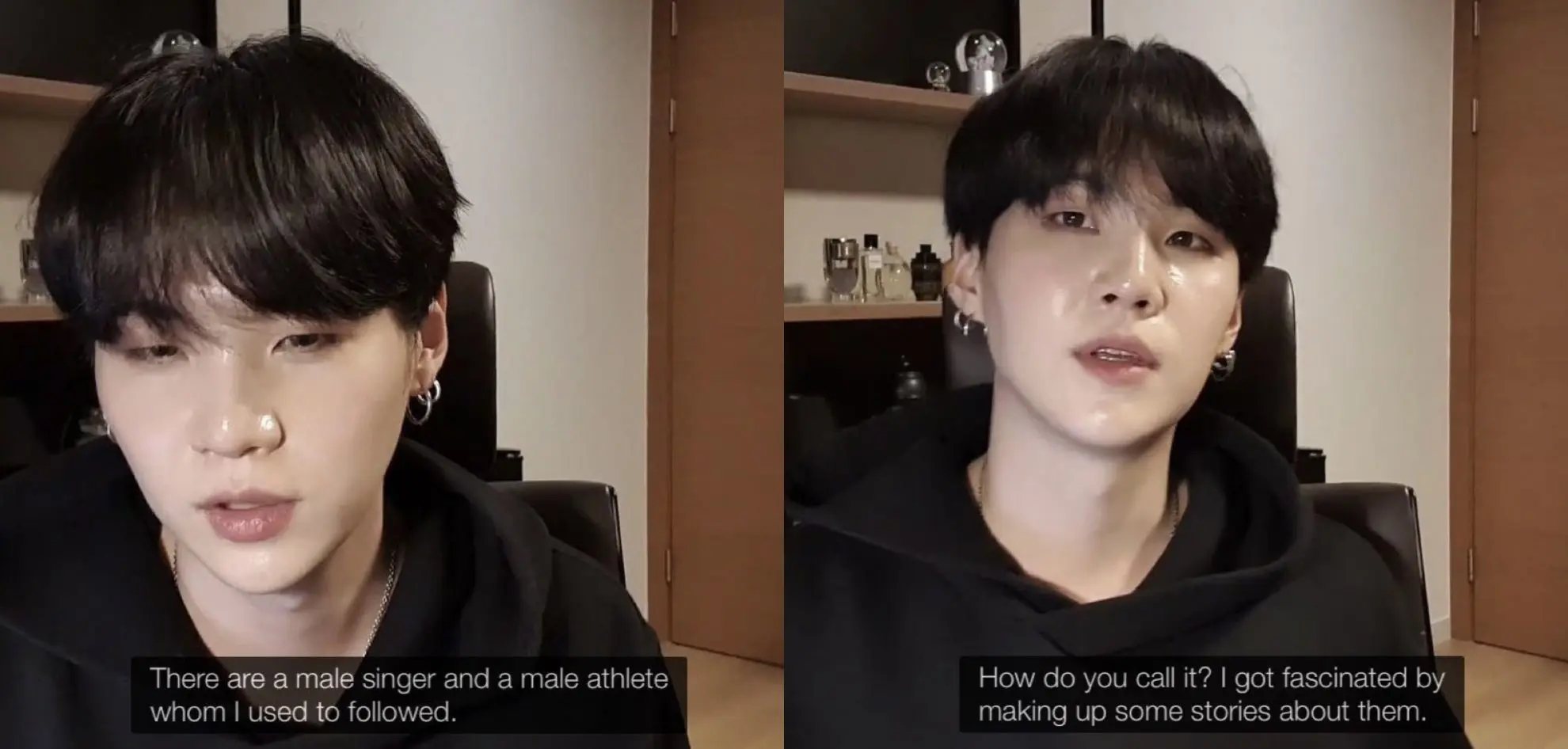

Do you remember 2020? More specifically, do you remember 28 May 2020? That was the night you livestreamed to talk to your fans about your latest mixtape D-2. You also said during your live that you used to make up stories about a male singer and male athlete that you liked. Yoongi, did you just admit to writing slash fanfiction?1 I didn’t know it was possible to like you more. My first ‘published’ writing was Harry Potter fan fiction at the age of 11. Nothing exciting, just the usual Ron/Hermione vanilla narrative, but written before I knew the pairing was canonical (and before we all knew Rowling’s anti-trans bigotry). Is this letter to you my attempt again at fanfiction, albeit in the context of an epistolary curatorial essay?

Sincerely Yours is a group exhibition that was borne from devotion and love, to examine the intersections between fandom and artistic practice. The exhibition came to fruition because, when I was aching to breathe and survive, you were there to pull me from the dark. When you told me that “it's okay not to have a dream” and that “just being happy is fine”, you told me I was enough. You helped shift the goalposts of what I wanted from this fickle life.

I know you understand the power of fandom. Fandoms and hobbies can offer us a salve or a momentary distraction from the harsh realities of daily existence. There is a reason why Pokémon cards have skyrocketed in price during the last two years, and why so many of us are finding nostalgic comfort in childhood icons. Encountering the works of artists Carly Snoswell, Daniel Pace and Jenny Ngo, I relish in their expressions of role models from my 1990s childhood. From Disney princesses, Nintendo heroes, to the first feminist I saw on the screen (Lisa Simpson), these works remind us of the long-enduring impact of characters from popular culture in our everyday lives. By the way, did you know that Mario is more recognised than most political leaders of our time? (Sadly, Trump still trumps Mario).

Fandoms can be sacred spaces, because they are built in imagination. They can provide a means of escapism, offering alternative realities that don’t yet exist. In this way, they share a commonality with artistic expression as a form of world-building. Don’t you think that the BTS universe enchants fans precisely because the worlds you and your bandmates have built through songs, lyrics, and music videos continue to inspire theories? World-building is at the centre of Nick Capaldo’s intricate works on paper, drawn from Star Wars films, which demonstrate the artist’s ongoing interest in imagining these intergalactic encounters. Fantasy is also present in Danny Lyons’ music video, which introduces us to the artist as singer/performer, taking cues from popular music production. There is something joyous about belting your heart out to your favourite song for all to see.

You might also recognise the main subject of Dylan Goh’s video installation as one of your bandmates – Kim Taehyung. Goh’s pastel dreamscape is an expression of queer fantasy: imagining a world where the artist and the idol are companions, travelling the world together. Speaking of idols, Ari Tampubolon uses the dance choreography of TWICE2 to express fannish devotion, while simultaneously challenging the white cube of the gallery space. Because of course, the cultural context of our fandoms are not neutral spaces – far from it. You would know this first-hand, having experienced racism and xenophobia because your band doesn’t fit into the dominant Western music industry’s shallow understanding of white excellence. Existing as a person of colour in these modes of cultural production, do we have to be 10 times more exceptional, to be the exception?

While fandoms can be built on fantasy, they can also act as a means to form real, lasting connection and community with others. The works of Alanna Dodd and Miles Howard-Wilks express this through their connection to one of the largest communal fandoms in contemporary life – football teams. When I first moved to Melbourne, this was one of the biggest cultural adjustments I had to make. I don’t understand the phenomenon entirely, but I do understand the devotion to shared successes – is this not why when you win music awards, you say that the award is because of us, your ARMY3? There is a vulnerability and tenderness that comes from giving form to our everyday desires, particularly when these expressions are shared with a larger community. This is the power of fandom, right? Not in the singular, but in the global. Fandoms have the potential to challenge existing hierarchies and power structures by banding people together under shared goals. And that is what makes them revolutionary too. Revolutionary in the sense that love is revolutionary, world-building, and powerful. You should know, you’ve written countless love songs.

I might be biased, but I think it takes courage and commitment to devote yourself to any fandom, to tell the world "this is what I care about and why." I love people that love things deeply – is this why I love you? Maybe I’m a romantic idealist, but what is the point of existing on this world if not for these small moments, when you can excitedly recognise something that makes your heart full? When Mel Dixon tattooed the works of her favourite artist and writer on her chest, she literally inscribed them close to her heart for all eternity. This reminds me of the line in your 2015 song ‘Intro: Never Mind’ where you rap: "It’s not easy but engrave it onto your chest." It’s a bold display of sincere intimacy, which is perhaps the reason why your bandmate Park Jimin did later get these words tattooed on his chest. And when Raquel Caballero meticulously hand-quilted a death portrait of Frank Sinatra, she is similarly inscribing her own devotion and sincerity to the subject of her work.

But it would be remiss to talk about fandom, without also acknowledging that like other expressions of love, it can be mutable, cause heartbreak, and change. Fandoms can be sources of immense joy but also incredible pain. While this exhibition does celebrate the motivational power of fandom, I am all too aware of how the lines between love and commodity culture under capitalism can produce ethically ambiguous zones. You aren’t a stranger to this, Yoongi, your company releases new merchandise featuring your face every other week – my home is filled with so many photos of you to the point where visitors ask if you are my relative. In Amy Meng’s soft sculpture, the cartoon-like figure at the centre acts as a stand-in figure, representing at once the simultaneous infantilising and sexualisation of Asian women in popular media. This is the danger of these one-sided expressions of love, particularly ones that position youth as something to be consumed. Being a feminist and a #casualfan of idol culture is the contradiction that keeps me up at night. It’s not your fault, but it is the flip side to this life I’ve chosen with you.

Despite this, or because of this, why do I still write to you? Why do I still try to reach out through the void between idol and fan? Perhaps it is in these flaws and moral ambiguities, that fandoms can teach us valuable lessons about what it means to live and love. That feelings don’t have to last forever to be meaningful, and that sincerity, nay, being afan about something, is actually a pretty incredible expression of optimism in these trying times. This exhibition would not exist, if it was not for this. And in this way, this exhibition would not exist, if it was not for you.

Mostly, what I love about loving you, is that it does motivate me to be a better version of myself. I don’t need you to know me, to know that this made an indelible impact on my life. Being a fan, opening myself to the joy and pain that this has brought me, makes me a better person and curator. By bringing these feelings into this exhibition, I hope I can be a part of a show that is guided by vulnerability, care, and radical joy, to challenge the elitism and snobbery of the so called ‘art world’ where having big feelings is often trivialised or dismissed.

Thank you for making me proud to call myself your fan.

Borahae4,

💜 Sophia

Sophia Cai is an curator, arts writer, part-time academic, and full-time ARMY based in Narrm/Melbourne, Australia. She currently teaches as a sessional lecturer in Critical and Theoretical Studies, Victorian College of Arts at the University of Melbourne, while also maintaining an independent curating and writing practice. Sophia is particularly interested in Asian art histories, the intersections between contemporary art and craft, and feminist curatorial methodologies and community-building as forms of political resistance.