Sebastian Henry-Jones

“A popular game for the people”

A large part of Tintin Cooper’s practice is centred on the idea of populism. Drawn to the pageantry of the sporting field and boundless reach of the Internet, in many ways her work investigates the culture of spectacle, the collective meanings and myths that develop around events over time through visual imagery, and the lives of these images as they circulate through real and digital infrastructures.

Unsurprisingly, Modern sport – a mode of collective witnessing that emerges when competition transforms into spectacle – has evolved concurrently (and to my mind most likely symbiotically) to the development of Modern image-based technologies; photography, film, mass media, the Internet and social media. Once upon a time, an individual had to be at the stadium to witness a sporting event with their own eyes. With the advent of live television, sport was transformed into something that anyone with access to a television could witness alongside the rest of the world in real time. The invention of the Internet and rise of social media today mean that events can be replayed, interpreted and mythologised on different timelines, dependent upon the viewing habits and situation of individuals dispersed throughout space and time. Today, sporting moments captured on camera are encountered in complex, decentralised patterns, and come to be understood in ever-divergent ways that far outstrip the plural dimension originally brought to life by television.

Zinedine Zidane’s professional footballing career began in Cannes – home of the renown film festival – in France’s Ligue 1 in 1998, and ended in 2006 at the World Cup Final. ‘Zizou’ finished that game early with perhaps the most infamous example of his hot-headedness: He headbutted Italian defender Marco Matterazzi in the chest, receiving a red card. France would go on to lose the game.

I was in high school at the time, and remember footage of the incident reproduced everywhere, in television, print newspapers and online. Youtube had been invented a year before in 2005, and I remember watching replays on the platform in the library with my school friends. And so, while the majority of his footballing career had been followed along by viewers on mainstream television, Zidane’s headbutting incident constituted an early ‘viral’ online event. The earliest video upload pertaining to the incident I could find on Youtube dates back 18 years (2006), while the latest was uploaded only eight hours ago at the time of writing. Clearly, the incident lives on in perpetual and variegated ways.

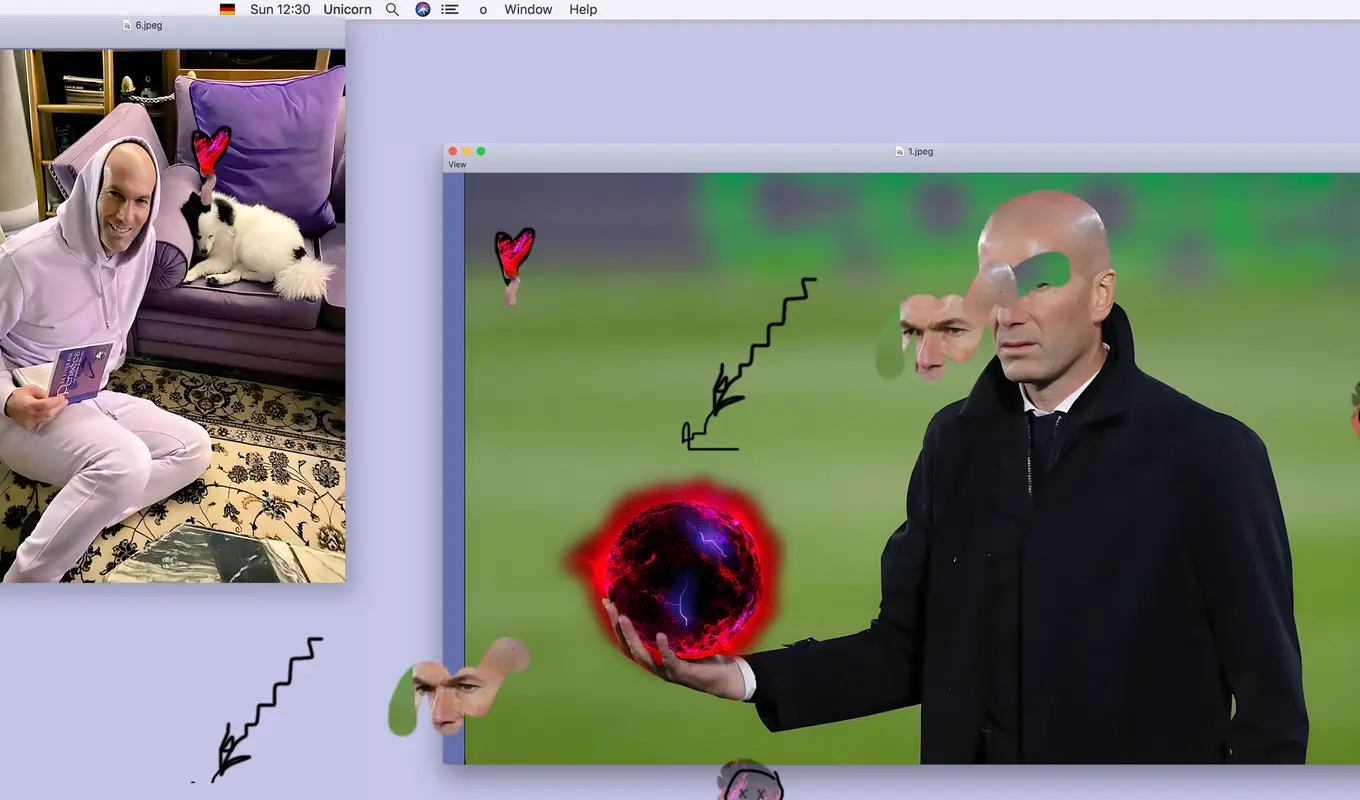

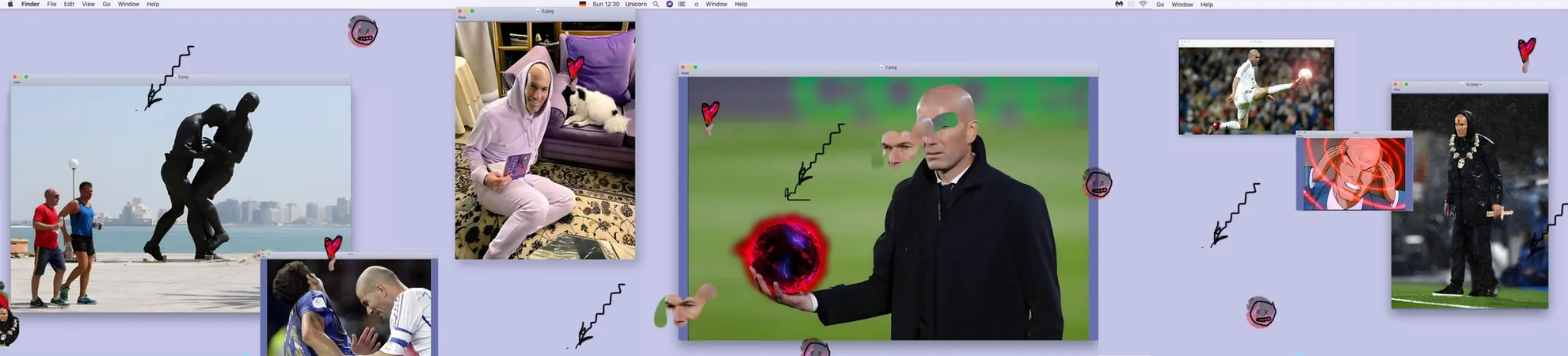

Tintin has previously referred to the many ways that images are ‘remixed’ on the internet, referring to how their forms are appropriated by different users, but also to the way that the context surrounding their appearance to an individual changes depending on their positionality in time and space. The co-option of American artist Matt Furies’ Pepe by the Manosphere provides for endless transformations of the original imagery of the layabout frog for example. Particularly troubled re-imaginings of this image also suggest that the material realities of their creators are characterised by isolation and a general misanthropy. Tintin was at art school around the time that Youtube first established itself. The lives that images go on after their creations (and following this, the lives of those people in them) has become one of the driving parts of her practice. It’s fitting that her research manifests in the narrative told by a selection of images of Zinedine Zidane – sporting figures, notably footballers and football managers – have long been the subject for different bodies of work because of their visibility in images across the UK, where the artist undertook her studies.

Widely regarded as one of the greatest and most elegant midfielders to ever play the game, digitally manipulated images of Zidane circulate regularly on the internet in ways that evidence his skill, and the mysterious powers that make his artistry on the field possible. The son of Algerian migrants to France, the player experienced racism regularly throughout his career, only to unite the country in 1998 when the national team – made up predominantly of players whose familial homelands had once been colonised by France – won the world cup. Narrative arcs like these in the professional life of Zidane (his legendary and trophy-laden career as manager of Real Madrid, the famous club for which he also played), lend themselves to endless adaptation on the internet.

The origins of paparazzi culture date to 1950s Italy, settling into a worldwide phenomenon well before the emergence of Zidane. As with Hollywood celebrities and members of England’s Royal Family, for decades, cameras have watched his every move on and off the pitch. In the 21st century, online football fans remix historical and contemporary images of the man to comment on his career, on his person or to lend weight to their footballing views. Wading upstream, against the digital flow of images in which there seems no rhyme nor reason, Tintin Cooper’s Black Magic – a title that references a corner of the internet that insists on Zidane’s access to an ancient footballing power – codifies the many faces and timelines of Zidane into narrative form, from which meaning can be made.

Sebastian Henry-Jones is the Curator at West Space. His curatorial approach is led by an interest in DIY thinking, and situated in the context provided by the gentrification of Sydney and Melbourne’s cultural landscapes.